Understanding Patellar Luxation

– Dr Karin Davids

Patellar luxation (dislocating kneecap) is the second-most common cause of lameness in dogs that we see (cruciate ligament disease being the most common). While some cases occur due to trauma, the vast majority (approx 95%) are due to inherited developmental disease.

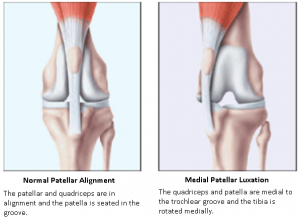

In order to understand how patellar luxation occurs, you need to know some basic anatomy. In the hind limb of the dog, the quadriceps mechanism is a large muscle group that extends from the hip joint, along the front of the femur (thigh bone) and connects via a strong tendon to the top of the tibia (shin bone). The patella is a small bone that sits within the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, and runs along a groove (called the trochlea) in the lower part of the femur. A straight alignment of the quadriceps muscle over the shaft of the femur is required to keep the patella tracking normally in the trochlea of the femur until it joins on to the tibia. Anything that changes the alignment of the quadriceps relative to the femur can lead to luxation of the patella. This alignment discrepancy starts with abnormalities of the anatomy of the femur and/or tibia, and during growth, the strong pull of the quadriceps mechanism causes progressive secondary changes (both bending and torsional) to the developing bones, exacerbating the degree of deformity. There is usually a combination of hip angulation abnormalities, bending and torsion of the femur and torsion of the tibia. Along with this, underdevelopment of the trochlear groove and tightening of the soft tissues around the area also occur. The progression of these developmental abnormalities is often worse in larger dogs (the longer the femur, the greater the lever arm between the axis of the femur and the axis of pull of the quads).

|

The patella can either luxate laterally (to the outside of the knee) or medially (to the inside of the knee). Luxation is graded from 1 to 4, based on severity. This article will discuss medial patellar luxation (MLP), as this is the most common presentation.

Symptoms of MLP

MLP affects knee extension, resulting in lameness, pain and progressive osteoarthritis. It also increases strain on the cruciate ligament and can increase the chance of cruciate disease or rupture. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, depending on the grade. The most common scenario is an intermittent “skipping” hind limb lameness. Some dogs will have no symptoms at all. Those with higher grades may have moderate to severe gait and conformation abnormalities.

How is it diagnosed?

We can make a diagnosis of MLP and its Grade by examination and palpation of the knee joint and patella. In addition, we assess for conformational abnormalities and other orthopaedic concerns (eg. cruciate ligament disease). Dogs with conformational abnormalities and higher grade luxations often require X-rays (or CT scans in more severe cases), to accurately diagnose the bony abnormalities and formulate a surgical plan.

Does my dog need surgery?

Does my dog need surgery?

This is a tricky one as there is no hard and fast answer. Each case needs to be individually assessed based on age, breed, symptoms, degree of luxation, and severity of bony abnormalities. As a generalisation, dogs most likely requiring surgery are:

– Young dogs less than 11 months, (especially larger breeds)

– Symptomatic dogs with Grade 1-2 luxations

– Dogs with Grade 3 and 4 luxations, plus or minus conformational abnormalities

– Dogs with a progression of luxation Grade

– Dogs with concurrent cruciate ligament disease

Asymptomatic dogs with low-grade (1-2) luxation may not need surgical correction, but should be monitored for progression of Grade, clinical symptoms and evidence of osteoarthritis.

What surgery is required?

The overall objective of surgery is to realign the quadriceps mechanism, and there are a few different approaches to achieve this.

1. Traditional surgical repair

In the majority of cases with Grade 1-3 luxations that do not have marked angulation or torsional abnormalities of the femur and tibia, we use a combination of some or all of the following procedures:

– Deepening of the trochlear groove – a section of bone is removed from the trochlea of the femur and then recessed back into the bone to create a deeper groove for the patella to run in.

– Tightening of the joint capsule on the outside of the knee joint.

– Realignment of the attachment of the patellar tendon at the top of the tibia bone – this is done by cutting the tibia where the tendon connects, and reattaching it in corrected alignment via two bone pins, plus or minus wire.

– Release of contracted soft tissues on the inside of the knee joint.

The overall results of this surgery are generally very good, with significant improvement of limb use and lameness. There is, however, a potential failure rate, especially in larger dogs and dogs with higher grade luxations. Some cases may get improvement in the Grade of luxation rather than complete normalisation of it. Despite this, the long-term outcome is good to excellent in 94% of cases in the hands of an experienced surgeon.

2. Dogs with concurrent cruciate ligament disease

Either a combination of the above procedures and a cruciate ligament stabilisation procedure (Tightrope or deAngelis), or a modified TPLO procedure is performed for these patients. Decision-making for appropriate surgery is based on the size of the dog, severity of patella luxation and degree of angulation of the top of the tibia.

3. Patients with high-grade luxations and angular/torsional deformities of the bones

In this situation, the severity of conformational deformity exceeds the ability to re-establish quadriceps alignment by traditional surgical repair. In these cases, realignment is achieved via straightening the bones by cutting them and fixating them in correct position with bone plates. Most commonly, this involves realignment of the femur (a procedure called Distal Femoral Osteotomy), either alone or in combination with some of the traditional procedures. In dogs with excessive torsion of the tibia, this bone may need to be cut and realigned as well.

Dogs that are more likely to require this approach include: Larger breeds, those with Grade 4 luxations, and patients with pronounced bending or torsion of either the femur alone or both the femur and tibia. In these cases, it is generally beneficial for Xrays to be performed prior to the day of surgery to aid in individual surgical planning. Note that certain breeds are overrepresented in bending and torsional abnormalities – both French and English Bulldogs are examples of this.

In some cases, grey areas exist where it would be of consideration to start with a traditional surgery but progress to an osteotomy surgery if the result is inadequate.

Prognosis

Reluxation after surgery is a recognised complication – in some cases, there is only so much that we can correct their conformation. Not all cases of reluxation result in clinical lameness – approximately 68% of reluxations are only Grade 1, and 92% of these are sound.

Minor complications occur in up to 8% of cases, and include pin migration or breakage, or discomfort from the implants. This is usually resolvable with medication or by removal of the pin once the bones have healed.

Regardless of which surgical procedure is performed, osteoarthritis of the knee joint is a progressive condition, and may require some ongoing management, especially later in life.